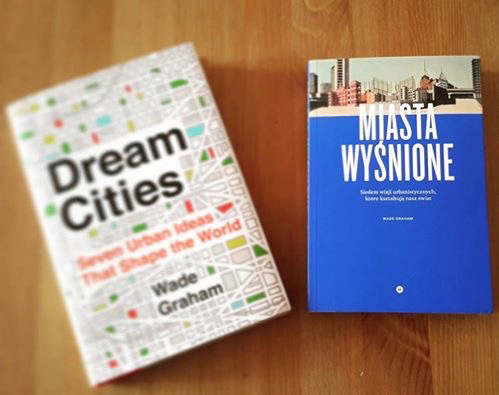

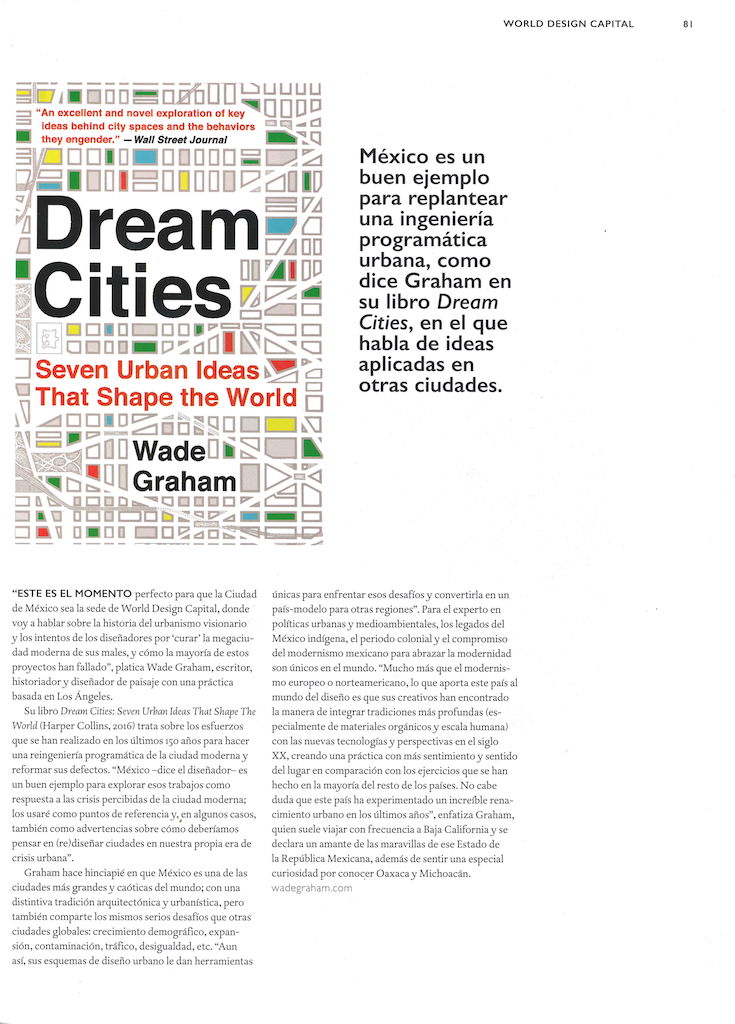

About Dream Cities

From the acclaimed landscape designer, historian and author of American Eden, a lively, unique, and accessible cultural history of modern cities—from suburbs, downtown districts, and exurban sprawl, to shopping malls and “sustainable” developments—that allows us to view them through the planning, design, architects, and movements that inspired, created, and shaped them.

Dream Cities explores our cities in a new way—as expressions of ideas, often conflicting, about how we should live, work, play, make, buy, and believe. It tells the stories of the real architects and thinkers whose imagined cities became the blueprints for the world we live in.

From the nineteenth century to today, what began as visionary concepts—sometimes utopian, sometimes outlandish, always controversial—were gradually adopted and constructed on a massive scale in cities around the world, from Dubai to Ulan Bator to London to Los Angeles. Wade Graham uses the lives of the pivotal dreamers behind these concepts, as well as their acolytes and antagonists, to deconstruct our urban landscapes—the houses, towers, civic centers, condominiums, shopping malls, boulevards, highways, and spaces in between—exposing the ideals and ideas embodied in each.

From the baroque fantasy villages of Bertram Goodhue to the superblocks of Le Corbusier’s Radiant City to the pseudo-agrarian dispersal of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Broadacre City, our upscale leafy suburbs, downtown skyscraper districts, infotainment-driven shopping malls, and “sustainable” eco-developments are seen as never before. In this elegantly designed and illustrated book, Graham uncovers the original plans of brilliant, obsessed, and sometimes megalomaniacal designers, revealing the foundations of today’s varied municipalities. Dream Cities is nothing less than a field guide to our modern urban world.

Illustrated with 59 black-and-white photos throughout the text.

Dream Cities: Seven Urban Ideas That Shape the World

Wade Graham

Harper Collins

195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007, www.harpercollins.com.

2016. 336 pages. Hardcover, $29.99

A note on buying local:

“When you buy from local independent booksellers, you support a small business that supports your community, and community in general, and conversation, browsing, discovering books you might not suspect exist, small publishers, authors—the whole food chain of writers, readers, and civilization.” - Rebecca Solnit

REVIEWS OF 'DREAM CITIES'

NY Times SUNDAY BOOK REVIEW

‘Dream Cities,’ by Wade Graham

By MICHAEL J. LEWIS, FEB. 5, 2016

Thomas More’s “Utopia,” which appeared 500 years ago, in 1516, may have changed the world. But few of its readers, I suspect, have read the whole thing. Impatient to get to “the good part” — More’s fanciful description of his mythical island republic — they understandably skip over its garrulous prelude, a dialogue in an Antwerp garden with the sailor who reputedly discovered Utopia. They shouldn’t, for in many ways this is the most brilliant part of the book.

More begins with a fascinating critique of contemporary society. Why, he asks, does the supply of thieves never exhaust itself, despite Tudor England’s brisk practice of hanging them, sometimes 20 at a time? His unexpected answer is sheep farming: The lucrative new wool industry was encouraging landowners to drive tenants from their fields and out into the streets, where they could only beg, steal or starve. In the end, More’s real accomplishment was less the far-fetched society he imagined than his recognition of the seamless unity that links economics, crime, health and even architecture — and its corollary that reforms addressing social problems in isolation were doomed to fail.

The architects and planners profiled by Wade Graham in “Dream Cities,” his ambitious study of the forms and ideas of the contemporary city, come in two categories. There are those few, like Jane Jacobs, who drew the deeper lesson of “Utopia,” which is that one must approach the organic interconnectedness of society with humility and deference. A vast majority, alas, are like those who have only dipped into its second half, emerging as incorrigible believers in the power of rational thought, right angles and good intentions to perfect society. In this category fall Daniel Burnham, Robert Moses, Le Corbusier and all those who marched in the cause of urban renewal.

Graham’s argument is that the basic physical structures of our contemporary world that these men created, from the shopping mall to the picturesque suburb, have grown mundane through constant repetition, to the point that they barely register on the eye. A “remarkable, global urban monotony” has set in, everywhere from Singapore to Ulan Bator to Buenos Aires to Boston. A garden designer and historian, Graham wants us to see these urban and architectural forms afresh, not as the drab commonplaces they have become but as the work of visionaries “whose dreamed-of cities became the blueprints for the world we actually live in.”

“Dream Cities” is a “field guide” to seven of those visions, each given a one-word title. Three are specific building types: “monuments,” “malls” and “slabs” (high-rise towers). And three are urban forms, although in fact they are profoundly anti-urban. These Graham classifies as “castles” (his terms for romantic suburbs), “homesteads” (contemporary suburban sprawl) and “corals” (the neotraditional towns of the New Urbanism). “Habitats,” his last case study, is something of an outlier, somewhere between a building and a city. It refers to those self-contained high-tech megastructures that were briefly fashionable in the 1960s, only to be discredited by the energy crisis of the 1970s and then reborn recently in the form of “techno-ecologies.” Norman Foster’s provocative Gherkin building in central London is perhaps its best known representative. This, Graham tells us, in what is probably meant to be a hopeful note, is “without question, the way the world now wants to build.”

The modern shopping mall is the one architectural form in “Dream Cities” that is purely commercial in function, but even it, Graham argues, was visionary in its original conception. This was due almost entirely to Victor Gruen, the Viennese architect who fled the Nazis in 1938 and became America’s most prolific builder of malls and shopping centers. In 1943 he proposed a model shopping center in Syracuse that would have had a communal as well as a commercial dimension, including a post office, a library, a public auditorium and even a nursery school. His ideas were swiftly imitated and in the process vulgarized; in the end, the “communal” component of the mall shriveled down to a few benches and lampposts, which was a source of great bitterness to Gruen, who returned to Vienna in 1968. For the rest of his life, whenever described as “the father of the mall,” he reacted with wrath: “I refuse to pay alimony for those bastard developments.”

“Dream Cities” is one of those books with a strong schematic concept that does not always work in execution. When an architectural form, its creator and a particular vision of the city neatly align, it serves readers well, as in the section on Frank Lloyd Wright, whose proposal for Broadacre City was a prophecy of modern suburbia. It functions less well with the great planner Daniel Burnham, whose pairing with monuments is forced (not only did Burnham design no significant monuments, it is not clear that he ever designed anything at all; his draftsmen snickered that they had never seen him with a pencil in his hand). Graham is better when it comes to his home state, California, which is often given short shrift in histories of this sort but is crucial to the understanding of 20th-century urbanism because of the dynamic way it adjusted to the automobile.

Especially vivid is Graham’s account of the rise of California’s “Mediterranean” style, which he traces to an astonishing study trip undertaken in 1901 by the architect Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue and his client James Waldron Gillespie. The two men toured from Italy to Persia, riding on horseback from the Caspian Sea to the Persian Gulf, and “drank in the architecture and gardens of this prelapsarian Oriental dream world.” Goodhue transmuted this raw material into the movie-set eclecticism that would become the vernacular of early-modern California.

It is a daunting task to write the social and architectural history of seven different forms, and there are signs of haste: Burnham did not tackle the “projected location of the Washington Monument” in 1901; that monument had been completed in 1888. The Jefferson Memorial (completed 1943) was the “last major element” of the 1901 McMillan Plan for the Capitol Mall, not the Lincoln Memorial (completed 1922). And New York’s Flatiron Building (1903) was not “the tallest in the world” at the time, falling well short of the lofty Park Row Building.

In the end, “Dream Cities” is an unintentionally tragic book. The visionaries profiled here, with few exceptions, suffered from an overweening belief in the capacity of architecture to shape behavior and thus society. This is the persistent temptation, as old as the Renaissance, to associate a perfectly ordered society with a perfectly ordered geometry. It takes only a moment’s reflection to realize that this is foolishness; if it were true, then our veins and arteries would have a grid plan like that of Manhattan rather than the messy medieval street plan they actually have. Such was the insight of Jane Jacobs, who emerges by default as the sanest visionary in “Dream Cities”: the woman from Scranton, Pa., who brought down utopian city planning, armed only with a typewriter and a pair of eyes.

DREAM CITIES Seven Urban Ideas That Shape the World By Wade Graham, Illustrated. 323 pp. Harper/HarperCollins Publishers. $29.99.

Michael J. Lewis teaches at Williams College and is the author of the forthcoming “City of Refuge: Separatists and Utopian Town Planning.”

The Connoisseurs of Order

Wall Street Journal: Feb 20, 2016

Review in National Post (Canada)

How adopted Canadian Jane Jacobs changed city planning from ‘a tragedy of good intentions’

Robert Fulford| February 16, 2016 |

Lurking in the shadows of every modern world building, there’s a fierce argument about how it came to be. Theories clash, careers flourish then die, and young architects never cease to believe they can do it better than their predecessors. The victories and defeats in these Oedipal struggles are as crucial to humanity as the political campaigns to which we give far more attention.

Architectural movements are usually discussed one at a time, mainly by the adherents of a single approach. Wade Graham, a Los Angeles designer and cultural historian, sets out to consider several of the main trends in one book, Dream Cities: Seven Urban Ideas that Shape the World (Harper Collins) He’s written a skeptical account of high hopes and large disappointments but he delivers a fair assessment of how each dream was born and why it seemed promising for a time.

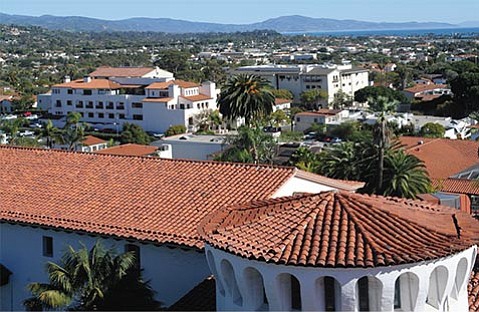

He describes, for instance, the modern imitations of the ancient world. He calls that style the Romantic City, relating it to the Mediterranean colours and forms he saw around his home when he was growing up in Santa Barbara. He traces that style to a trip made in 1901 by Bertram Goodhue, an accomplished architect who toured the Middle East and imported its images to create what became the California style.

Graham outlines Le Cobusier’s concrete slabs-in-a-park, Frank Lloyd Wright’s version of the suburbs and the Techno-Ecological City promoted by Kenzo Tange in Japan. Within that last group he includes Montreal’s Expo 67 for Moshe Safdie’s stacked apartments in Habitat and Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic U.S. pavilion.

These powerful styles, widely publicized and praised, become so embedded in the conventional wisdom that architects and builders sometimes unconsciously copy them. As John Maynard Keynes said about his profession, “Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.”

The present tense in Graham’s title, Shape the World, indicates that most of the theories he’s studied are still in use, often in a degraded form. People visiting China sometimes remark that the Chinese kept building poor imitations of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s modernist buildings long after they were discarded in their birthplace, the United States.

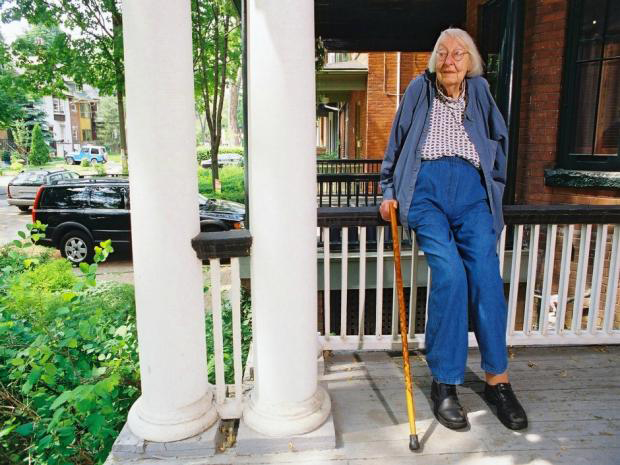

The heroine of Graham’s story is Jane Jacobs (1916-2006), the greatest adopted Canadian intellectual ever, who brought an original mind and a warm heart to this subject and sorted it out better than anyone before or since. She’s often been praised, deservedly, but rarely with the all-encompassing passion that Graham brings to her work.

She was the first writer who applied a critical intelligence to the failures of town planning. By the time she studied it, in the 1950s, the planning of cities was a tragedy of good intentions that were carelessly applied. Planners came to believe that cities needed to be re-thought from the beginning. Districts that were “blighted” should be torn down and replaced by logical constructions imagined by architects and planners in the name of Urban Renewal.

The new versions, as any architect could explain, would include tower blocks of apartments surrounded by large spaces devoted to parkland or schools. But Jacobs, who never went to university or studied planning, saw the results obtained by professionals who were blinded by theory. The empty spaces they planned turned out to be barren landscapes that people avoided as much as possible. The tower blocks were widely hated, crime-ridden and usually called “the projects.” These were the best that the best brains in planning and government could produce.

Where did these monstrosities come from? Jacobs singled out a major villain, Ebenezer Howard, the Englishman who founded the Garden City movement. He dreamt of Utopian projects that would create environments in which people lived harmoniously with trees and flowers. He felt that would reduce the alienation of humans from nature.

Jacobs decided that Howard’s many followers disliked streets and density and were therefore against cities. They considered the presence of many people “a necessary evil.” They favoured isolation and suburban privacy. She argued against Howard’s most dedicated advocate, Lewis Mumford. He had fallen for a Utopian dream that never existed or could exist in cities. Mumford replied condescendingly that she wasn’t trained in the field. But that was her great advantage.

She saw that successful streets were created through the trial-and-error accretion of human experience. They are self-organizing, growing organically like a coral reef building over time. They do not divide functions into separate zones, like so many town plans. They put work, housing, play, shopping, night life all in roughly one place. They may need help now and then but they do not need to be obliterated for the crime of being “blighted.”

A writer in the New York Times noted recently that in the war of ideas over the future of cities Jacobs brought down Utopian city planning, “armed only with a typewriter and a pair of eyes.” She saw the truth while researching magazine articles and drew her ideas together in 1961 in the first of her many books, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, a tribute to living streets, written in poetic and compassionate prose. It became the most important book of its time in city building.

A resident of Greenwich Village, Jacobs saved her own community and others when she defeated the “slum clearance” plans of Robert Moses and his proposed Lower Manhattan Expressway, which would have cut through several districts.

Later, when she and her husband moved to Canada so that their sons could avoid the Vietnam war, Jacobs saved her Toronto district, the Annex, by inspiring the movement to cancel the Spadina Expressway.

Wade Graham’s Dream Cities describes how easily many of us can be persuaded to approve misguided plans when they are presented by professionals with the proper credentials. The career of Jane Jacobs illustrates how much we need the humane understanding of original thinkers.

Review Of Dream Cities IN URBAN LAND

By Martin Zimmerman, August 15, 2016

This is a book that educates, entertains, and astonishes. It is an effort that progresses along multiple paths of utopian impulse, while at the same time gushing forth with a bravado of egocentric, architectural hubris. There is Le Corbusier, the Swiss Cartesian, who advocated for the destruction of Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s Paris. Or America’s Frank Lloyd Wright, whose dream was to destroy cities altogether. Or megamall impresario Jon Jerde, whose monuments to consumerism extend from Horton Plaza in San Diego to Dubai Festival City in the Persian Gulf. All the while, the deeper understanding of author Wade Graham, who also wrote American Eden, keeps such heroics from veering totally off course.

On one level, Dream Cities purports to be a “field guide” for a neophyte audience “to give the reader the tools to identify the architectures all around us . . . to read, decode, and understand.” To make the subject matter as accessible as possible, the book titles each chapter with a single word representing a building archetype, and then pairs that word to its protagonists. The chapters conclude with a set of descriptive illustrations and a brief checklist of the archetype’s characteristics. For instance, it begins with “Castles” (Bertram Goodhue and the Romantic City) and is followed by “Monuments” (Daniel Burnham and the Ordered City), with several other chapters following.

More than anything else, Graham’s insightful narrative reveals the contrast between the seminal dream and the dream’s unintended consequences. As one navigates from archetype to archetype in Dream Cities, it becomes increasingly evident how much has gone awry. Many of the questions the author poses—sometimes skeptically, other times inquisitively—cannot be answered by a camera click or the stroke of an air brush. Rather, they serve as a portal to larger questions about whether some measure of human dignity can be salvaged from a global village that is simultaneously shrinking and expanding at a dizzying pace.

Of Bertram Goodhue’s romanticized urbs of the early 20th century: “What was new was a kind of city built on the illusion that it wasn’t a city—a city dressed as the country . . . each a castle standing alone in pastoral splendor.” Of Frank Lloyd Wright’s vision for Broadacre City, Wright apprentice and a utopian of his own, Paolo Soleri, had this to say: “There’s nothing as consuming as suburbia. It’s a . . . colossal engine of consumption . . . if Mr. Wright were alive now, he would have changed his rationale.”

Of the fallout from Le Corbusier’s Radiant City, Graham points to a mid-rise behemoth in Gdansk, Poland, that is 3,000 feet (914 m) long and houses 6,000 residents and to the Kin Ming high-rise nightmare in Hong Kong, housing 22,000. And he joins the new urbanist skeptics in drawing a wry parallel between a crispy clean, form-based new town called Celebration and the daffy cinematic spoof The Truman Show.

Dream City has its downsides. Until the very end, Graham honors the basic truism espoused by Jane Jacobs and others that—except in memory and imagination—a city is rarely, if ever, a work of art. To quote Jacobs: “To approach a city . . . as if it were a larger architectural problem, capable of being given order by converting it into a disciplined work of art, is to make the mistake of attempting to substitute art for life.”

And then, on the very last page, the author falters with an embrace of the eco-corporate idiom of Lord Norman Foster, designer of the iconic, high-tech “Gherkin” tower in central London. “Foster’s oeuvre, following in the footsteps of Fuller, Sadao, and the Metabolists . . . has become, without question, the way the world wants to build.” One wonders: Has Graham succumbed to more utopian delusions than even hecares to admit?

As far as American suburbia is concerned, the author overlooks the fact that many escapist, romanticized suburbs of the past few generations have, of late, turned out to be quite transit-friendly, densified, and socially diverse. One may hate to admit it, but yesterday’s genteel sprawl sometimes becomes today’s urb . . . or visa versa.

Minor shortcomings aside, Dream Cities deserves to be savored in one sitting, and it matters little whether the reader is a seasoned student of cities, a “flaneur,” or merely a curious bystander.

Martin Zimmerman writes frequently for Urban Land from Charlotte, North Carolina.

A red tile roof in the University Grove housing tract in Redlands. (Staff photo by Rachel Luna)

Los Angeles Daily News / Opinion

By Larry Wilson, San Gabriel Valley Tribune 02/19/16

How California architecture longs for soul of old Spanish dayS

I had long known, as every Southern Californian knows — whether intuitively or from book-learnin’ — that the received architectural style in these parts, red-tile-roofed and vaguely Mediterranean, often has more to do with the movies and the movie business than with old Spain.

It’s actually more Megaterranean, as my architect friends humorously deride the cookie-cutter mansion-tract sprawl from sea to Salton Sea.

But I hadn’t known, until reading Los Angeles historian Wade Graham’s new book “Dream Cities: Seven Urban Ideas That Shape the World,” that the whole shooting match can be traced to one long trip that the great architect Bertram Goodhue took with a wealthy client in 1901, “through Italy, the Levant and Persia, where they rode 800 miles on horseback from the Caspian Sea south to the Persian Gulf.”

When they came back, Goodhue built for that client, James Gillespie, an extraordinary mansion in Montecito called El Fureidis, a polyglot palace combining Spanish, Byzantine and Iranian influences. You’ve never seen anything like it, and that was the point. Graham writes that “it was arguably the first ‘Mediterranean’ house in California” when it was built in 1906, “an entirely new form, both historicist and paradoxically modern.”

This holds true for the rest of Santa Barbara, which many visitors somehow believe — and are encouraged to believe — was Spanish Colonial in style since time immemorial. Actually, as Graham, who is from Santa Barbara, notes, the resort city on the Pacific was mostly “Victorian eclectic” until the earthquake of June 1925 leveled almost the entire downtown, following which a new architecture review board made red tiles and whitewashed walls virtually the law. Sure, there was the mission, and the De La Guerra adobe. But they were the exceptions until they became the rule, a move applauded by the Hollywood film community, which had taken to weekending up the coast, and for whom there was no reason to differentiate fantasy from reality. It’s one of the loveliest movie sets ever built.

Goodhue, after his first red tiles, went on to create the extraordinary baroque mock-Spanish city in San Diego’s Balboa Park for the Panama-California Exposition in 1915 in the heart of what was then a city of 35,000 people, and no wonder everyone in the world wanted to move there after seeing it. He also developed an early concept for the Caltech campus, and the fantastical Los Angeles Public Library.

None of these places are modeled on a real Mediterranean locale. But all of them are the reason that, as the ad copy promoting a fancy hotel called Pelican Bay reads, we today still desire to take “a trip to Italy by way of Newport Beach.”

Does it matter that almost every new development from Porter Ranch to Azusa to Rancho Cucamonga is built in this red-roofed style, a century since Goodhue brought it back to us? Of course it does. The way we want the places in which we live to look are the outer expressions of our innermost desires about telling others who we are or who we aspire to be. And, yes, along with the real Mediterranean and small parts of South Africa, we are home to one of the few climates similar to that cradle of civilization.

But we might as well know how the rest of the world sees California, and Graham quotes the great East Coast cultural critic Edmund Wilson writing as early as 1932 a “remarkably inventive bit of snobbish ridicule” about our architectural choices: “And there a hot little hacienda, a regular enchilada con queso with a roof made of rich red tomato sauce, barely lifts her long-lashed lavender shades on the soul of old Spanish days.”

LA OBSERVED

City of irreconcilable dreams

By Jon Christensen | March 19, 2016 10:09 AM

"Putting our best efforts into reforming the built environment as the means to reform ourselves and society is a remarkably deeply held belief in our culture, as if we modern urban dwellers are a cargo cult, putting faith in things to transform our souls and spirits."--Wade Graham, Dream Cities: Seven Urban Ideas That Shape the World.

Wade Graham's new book, Dream Cities, is a cautionary tale. It ranges widely through time and around the world. But it's aimed straight at Los Angeles, the author's hometown, right at our present moment.

Big dreams promising to transform our city are all the rage these days:

Frank Gehry is reimagining the LA River!

More than $120 billion in new funding for Metro will remake the way we move around LA! (If voters approve a sales tax increase in November.)

The Olympics will make LA a world-class city! (Again!)

The Third Los Angeles is on the way!

Graham's book is not explicitly about these new dreams. But it is about dreams that have shaped--and continue to shape--Los Angeles, and how people expect the built environment, a product of urban ideas, to shape our lives, indeed even our souls and spirits. Like all good histories, Dream Cities is about unintended consequences.

Graham is a landscape designer and writer. He lives in Echo Park and teaches at Pepperdine.

When he looks at Los Angeles, he sees a city of irreconcilable dreams.

All of the big urban ideas that he traces in Dream Cities are at work here in LA:

The "romantic city" of the Spanish colonial villa, which can be seen most clearly in Santa Barbara, of course, but also in Beverly Hills and other wealthy redoubts around LA, where an imagined past confers the aura of historical legitimacy on a contemporary order.

The "monumental city" of well-ordered boulevards, stately plazas, and trophy buildings, which can be seen around Grand Park, City Hall, the LA Times building, the Music Center, and most dramatically in Walt Disney Concert Hall, which manages the neat trick of looking futuristic while fulfilling the role of a monument reflecting "glory and gravity" back on the city and those who preside over it.

The "rational city" of modern skyscrapers, "slabs" Graham calls them, connected by freeways. "A city made for speed is a city made for success," wrote Le Corbusier, the godfather of this dream. We see it in on Bunker Hill, in Park La Brea, and Century City.

The "anticity" of "homesteads" seen everywhere in LA's most dominant form, the single-family home, sprawling ever outward, as people seek to be part of the city, but apart from it. Its most iconic form shows up beautifully in the famous nighttime image of the Stahl House (Case Study House #22), where two women sit serenely conversing in a modern home cantilevered over a hillside, with the parallel lights of the city's streets receding into the safe and scenic distance.

The "self-organizing city" of neighborhoods, "cities within cities," epitomized in the apocryphal critique that Los Angeles is "72 suburbs in search of a city," variously attributed to Dorothy Parker, Aldous Huxley, and H.L. Mencken. But also in what all of us who live in the city know, that LA can be a very different city depending on which neighborhood you are in.

The "shopping city" of malls, in which "maximizing shopping equals maximizing urbanism," seen here from Third Street in Santa Monica, to the Galleria, the Grove, CityWalk at Universal Studios, and more.

The emergent "techno-ecological city," conceived as a kind of isolated space station in a harsh environment, concerned with the "metabolism" of the city, sustainability, water conservation, recycling, production of food and energy, and a changing climate.

Los Angeles isn't shaped by any one of these big ideas alone, Graham told me. Instead, LA is a city of "dynamic, problematic conflict between dreams," he said. Los Angeles is driven by contradictory ideas "that don't mesh well with each other."

So why are we now hoping that some new idea might somehow save the city?

"We buy into the promise of ideas," Graham said. It's easier than the hard work of "democracy, citizen participation, and boring things like that," he added. "And it leads us astray most of the time."

Despite the failure of all of these ideas to live up to their promises, Graham said, we still would like to believe that changes in the built environment could somehow miraculously solve all of our urban problems.

There is a "social project" inherent in all of the urban ideas that Graham writes about in Dream Cities. The architects and planners he profiles all believed that the right built environment would create better people, a better society, from Daniel Burnham's "Make no little plans, they have no magic to stir men's blood...." to Jane Jacobs, who fought big plans on behalf of little neighborhoods.

"We put an incredible freight of meaning into objects that don't really deliver," Graham said.

What we really need to do instead is "disenchant our objects," because if we keep acting like a cargo cult, praying that the next big idea to fall from the sky will change our lives and our city, we may be waiting forever.

Santa Barbara INDEPENDENT

Wade Graham on Living the Dream

Author Ponders Whether Santa Barbara Is the Original Dream City

Thursday, June 2, 2016 by Charles Donelan

What do San Diego’s Balboa Park and the Montecito Country Club have in common? If you answered that they are both quite pleasant environments, you are certainly correct, but if you said architect Bertram Goodhue, give yourself a rousing Spanish Colonial “olé.” In his new book Dream Cities: Seven Urban Ideas that Shape the World, historian and landscape architect Wade Graham makes the case that the extraordinary beauty of Santa Barbara’s carefully tended architectural identity began not in Spain or Italy, but rather in the imagination of Bertram Goodhue. Graham cites as evidence for this claim the detailed traveler’s reports that Goodhue created between 1896-1899 of “three romantic, out-of-the-way, overlooked sites that still boasted ancient examples of buildings and bygone patterns of life.” Goodhue rendered each of these locations — Traumburg, a medieval town in German Bohemia; Villa Fosca, a Renaissance villa with elaborate gardens situated on a remote island in the Adriatic; and Monte Ventoso, a hillside village in northern Italy with a church and a piazza — in exquisite ink drawings that showed not only the relation of the landscape to the architecture but also detailed architectural plans of the major buildings and carefully observed sketches of daily life. To these elaborate drawings Goodhue appended “lively notes” recalling visits and conversations with the people who lived in these towns.

What’s the catch? At the time, Goodhue had never been to Europe, and all three of these portfolios described not real places but fantasies, or “traumburgs,” dream cities conjured out of the young architect’s budding imagination. This, according to Graham, is the origin of our famed paradise of a built environment, the idea of a “new kind of place: one with the economic and social advantages of a city, but none of its disadvantages.” The book’s opening chapter goes on to describe El Fureidis, the fabulous estate in Montecito that Goodhue created for his patron, James Waldron Gillespie, as the prototype of the contemporary suburban “castle,” an independent single-family dwelling designed to connect one’s current socioeconomic status with an artificial and imaginary version of the distant past. Subsequent chapters look at a range of equally influential notions about what the city could or should be, from the neoclassical “monuments” that establish cities as seats of governmental power to the tall “slabs” characteristic of both financial centers and public housing. Each designation comes complete with an origin story detailing the career of a particularly significant avatar of the style: Frank Lloyd Wright and the “homestead,” urbanist Jane Jacobs and “corals,” which are mixed-use, code-controlled groups of buildings that share a limited range of historicist styles.

As urbanists go, Graham is definitely a contrarian. For every predictable hero, like Jane Jacobs, there’s a surprise, such as his admiring portrait of Jon Jerde, the man who created Universal CityWalk, Horton Plaza in San Diego, and the Fremont Street Experience in downtown Las Vegas. When I spoke with Graham recently by phone, he emphasized the fact that in his version, urban design “is all the same story — the real world has always been constructed by engineers of our desire, and we have always lived in the run-down detritus of their fantasies.” Even today’s obsession with green projects and sustainability looks like self-deception to Graham, who compares LEED structures to space stations, as they make “the same promise of disconnection from the negative environmental impact of human habitation.” “The intelligentsia leans toward the future” he told me, “and green cities are just the latest version of greenwashing our dependence on natural resources. As a society, we have a magical belief in the power of objects, and science is an extension of that cargo cult mentality.”

Asked about the immediate future of Santa Barbara, where he was born and grew up as a UCSB faculty brat, Graham waxes more optimistic, stating that, despite the threat of significant population increases, we are still better off than most, even those who reside in the supposed models for the American Riviera. “In many ways, Santa Barbara is better than Andalusia or Florence,” Graham said, adding that he has not written Dream Cities to denigrate the work of architects and urban planners, but rather to educate non-architects in the various concepts that drive the world’s most common urban-planning conventions. Although it is not one of the forms addressed in the book, Graham cites the “ranch burger” as the most typical residential concept in Southern California. “A ranch burger is a satisfying but off-the-shelf, one-story, single-family home with a front and backyard and a covered garage or carport,” Graham explains. Asked if the ranch burger is “sustainable,” Graham observes that, “there are already too many of them, especially in greater Los Angeles and in Orange County, because here in California, everyone wants to live like a hidalgo.” What are the consequences of the ranch burger explosion? “Crazy long commutes, bad traffic, you name it.” And the alternatives? “Skyscrapers in Westwood and apartment block towers in Santa Monica, and this is already developing into open conflict on the Westside of L.A. People in Hollywood don’t want to look at a skyscraper out of their living room window.” Asked if there could be a middle way between the Manhattanization of Los Angeles and a zero-growth policy, Graham said that he thinks there has to be a middle ground because “it’s the all or nothing dreams that are the sources of the biggest and most destructive failures.” In an attempt to end things on a bright note, I turned the conversation back to Santa Barbara by asking Graham, who lives in Echo Park, a hypothetical question. “Okay, imagine you’ve got a couple of million to spend, and you are going to buy in Santa Barbara. What is it going to be?” Without hesitating, he said “something on the west side of downtown, maybe on Bath Street, and with a courtyard. That’s the way we should be living here. Those courtyard bungalows are the real indigenous architecture of Central Coast beach towns.”

Review of Dream Cities by Blake Seitz, July 10, 2016

http://freebeacon.com/culture/field-guide-city/

I’m a dabbler by nature. A little Symbolist art here, a little classical architecture there. I have a conversational level of knowledge—or at least impressions—about many things, but a mastery of almost none. I will dip my toes in new waters and paddle around in the shallows, but I’m not going for the free diving record. I don’t have the lung capacity. Being a dabbler serves pretty well, living as one does in a world of opportunity cost and lively receptions where it pays to come armed with a reference or two. If you are reading this, I suspect you may be a dabbler, too. Culture sections attract a type of languid generalist.

Welcome, friend. I have a book for you.

For dabblers, nothing brightens the day more than finding a book that is a good entry-point into a field of study—that offers a way to think about that field and organize facts rattling around in the brain. Dream Cities by Wade Graham is such a book about urban planning and architecture. The book introduces readers to the schools of architecture that have shaped modern cities. It provides a taxonomy of those schools so readers can know them “by their plumage, their calls, their habitats, and behaviors” as they explore the urban jungle.

Dream Cities is organized into seven chapters. The title of each chapter introduces one or two architects and associates them with the Platonic Form of building they designed. For example, Le Corbusier built Slabs; Frank Lloyd Wright, Homesteads; Jane Jacobs, Corals; and so on.

Each chapter follows basically the same format. First Graham sketches the details of the architects’ lives, their bodies of work, and their conceptions of what a city should look like. Then he describes the impact those architects had on the cities we inhabit today—how their visions changed over time as they made contact with reality or were taken up by students. The first part of the chapter describes how the city ought to be in the brilliant studios of the architects’ minds; the second part describes how the city actually turned out in our eminently practical yet still brilliant world. The chapters end with “field guides” to the architectural styles, including bullet-pointed lists of common features and photographs of representative buildings. The photographs—while small and grayscale—are very helpful, this dabbler reports. The rather dense lists of features, less so.

The architects profiled in the book had visions that differed dramatically. Some were radicals, offering plans that would have effectively scrapped the world they lived in and started over again. Famously, Le Corbusier envisioned a hyper-rationalist hive society, or Radiant City, that segmented communities by function, connected the segments by ultra-efficient transit systems, and boarded inhabitants in soaring cruciform towers that were heavy on function and light on form. On the opposite end of the collectivist-individualist spectrum, Wright envisioned a radically decentralized network of self-sufficient homes connected by highways and overseen by benevolent, all-powerful city managers. Every family would receive at least a one-acre plot under this plan—like a Homestead Act for the twentieth century.

Both of these visions were too costly, ambitious, and in their own ways unworkable for city leaders to implement in full. They were implemented piecemeal instead. Le Corbusier’s ideas found expression in disastrous Urban Renewal plans featuring strictly-zoned business districts that turned into abandoned wastelands after 5 p.m. and housing complexes that isolated poor residents from economic opportunity and police protection. The Corbusian ideal—scarcely more attractive on paper than in practice—was “urbicide,” Graham states succinctly. Wright’s ideas found expression in the tract houses of suburbia, cookie-cutter structures that would have frustrated the oddball architect, who had hoped his plan would create space for individual expression and achievement.

Other architects profiled in the book were incrementalists whose visions did not require a blank slate. Victor Gruen and Jon Jerde, the godfathers of American retail, are the subjects of a curious chapter tracing the history of shopping malls from the Palais-Royal of seventeenth century France to the Mall of America in Bloomington. Gruen and Jerde harnessed the insights of psychology and marketing to create capitalist carnivals bustling with foot traffic and affordable attractions. More alluringly, these mega-structures offered shoppers the possibility to make and re-make their identities through shopping—an existential sales pitch, however shallow, that explains the mall’s status as a meeting place for teenagers in the 1980s and ‘90s, just as they were the strutting stage for flâneurs in Bourbon France.

There are many others, from the stirring civic monuments of Daniel Burnham to the conspicuous eco-consumption of Britain’s Lord Foster. Graham handles all this subject matter deftly, and presents it with relative evenhandedness. His allegiances are predictable and apparent—suburban forms are derided in the typical ways, while the defects of New Urbanism and ecological design are attributed to unscrupulous real estate developers betraying the revolution—but not distracting.

Graham’s choice of the term “field guides” is apt. Dream Cities is a field manual, or an especially lively introductory textbook to an interesting field of study. I recommend it highly to dabblers, urban explorers, and the chronically curious.

Profile in Pepperdine Magazine

“Urban Legend,” Cover story by Gareen Darakjian.

A childhood curiosity about the world around him propelled School of Public Policy professor Wade Graham into a lifelong exploration of the landscapes that define our lives.

“We are strangely well trained in our culture to not see what’s around us,” suggests Wade Graham, adjunct faculty at the School of Public Policy, landscape architect, historian of modern urban life, and author. In his latest book Dream Cities: Seven Urban Ideas That Shape the World, Graham laments that even the most educated individuals are unaware of and possibly apathetic to the structures that form the backdrops to their lives.

Graham grew up 90 miles north of Los Angeles, up the coast of California in Santa Barbara, an idyllic destination that has historically beckoned artists and visionaries to the tony enclave tucked between lush green hillside and deep blue sea, a sort of Mediterranean utopia lined with red-tiled roofs.

His childhood home was what he calls a “developer version” of a Case Study House, styled in a California mid-century modern design with glass walls, post-and-beam construction, and a Danish sensibility throughout. His mother, a professor, design enthusiast, and restaurateur, spent much of her time perfecting the abode and developing its garden in the style of Lawrence Halprin, a pioneer of modern landscape architecture. In a house soaking in postwar modernism, Graham was exposed to the ideologies of David Gebhard, an architectural historian and Santa Barbara architecture preservationist, by way of his father, himself a revered historian and decorated academic.

Graham’s foray into the study of urban landscapes was “osmotic,” as he explains, a product of growing up in a “very carefully constructed environment,” in which he became acutely aware of the surroundings that shaped his—and others’—everyday life.

During a leave of absence from PhD studies in comparative literature at UCLA, Graham was introduced to notable landscape designer Nancy Goslee Power, who hired him as an apprentice after learning of his knowledge of the cultural history of California, architecture, and graduate work in environmental history. On the job, he discovered the euphoria of gardening he calls “garden magic,” a feeling of wonder that hearkens to his childhood days of yard hopping through the bucolic properties that lined his Southern California neighborhood in the 1970s.

In his first book, American Eden (2011), Graham gives a comprehensive history of how modern landscapes came to be and how gardens influenced the environments in which we now live.

“There is no line drawn between environmental history and urban history,” Graham explains. “If you do an environmental focus, you’re engaging with urban issues, and in the U.S. in particular, you’re engaging with urban planning.”

The idea for his latest tome, Dream Cities, came to him in 2009 after teaching his first course on the history of American cities at the School of Public Policy, which dives into U.S. urban and environmental policy and attempts to open the eyes of his students to the world around them.

“We are knowledgeable about things that are portable, like cars or handbags, but not so much about nature or buildings,” he explains. “People are very unengaged with their physical environment. They structure our lives, but we’re blinded to it by training.”

In his class Graham builds a narrative around the forgotten landscapes that we so often utilize but never engage with, monuments and structures that were built to disappear into the background of everyday life. Students are led on field trips to sewage plants and the bed of the Los Angeles River, and are encouraged to contemplate freeway diagrams, all while using Dream Cities as an historical as well as a field guide. “It’s a revelation to us, because we’re not trained to do it,” he explains.

“A light bulb goes on when you realize you’ve looked at something your whole life and haven’t really seen it, and then you go ‘aha’ and understand the relationship behind it: who it serves, what it serves, what ideas it promotes, and what ideas it crushes,” Graham continues. “History, dynamism of environments … my hope is for people to stand in the middle of the street and be able to tell interesting stories about what they see. I’m trying to get people to see their mundane world in a new way.”

Dream Cities is Graham’s personal quest for an explanation for the kind of patterning seen in all modern cities and to shed light on the history of modern architecture, its intentions, its defining characteristics, and its power in shaping our lives. He discovered that, when you stop to look around or while traveling, many cities built in the modern era— which began in 1850—are constructed using the same pieces. The tower blocks, freeways, shopping malls, parks, and gated communities you may see in Los Angeles can also be seen in Minneapolis and Madrid.

“That needed explaining,” says Graham, who was also curious about the overlaps between different structural groups. “You can find a gated community that is also a mall, you can find a city hall that’s also a tower block. I wanted to understand where they came from. They’re kind of like species. They’re incredibly successful. They are the invasive species of the modern urban world.”

The book begins with an exploration of the pioneers who developed the modern world, how they promoted their ideas, and what assumptions their ideologies carry in society. “All of these things are an expression of some kind of idea about what will make life better,” Graham explains. “All of them are Utopian, or even prescriptive. Take the shopping mall: we think of it as a debased form, but the role of shopping architecture is as exalted as religious architecture. It’s the oldest one we have.”

In Dream Cities, Graham reveals that the origins of modernism led to the destruction of the traditional understanding of community and favored the restructuring of human life into segregated spatial zones. He explains that this allowed the modernists to organize society in mono-cultures. In other words, Graham posits that most of modern society’s social and ethical issues—religious divisiveness, childhood obesity, crime rates, incarcerations—are a direct result of the decisions of the original modernists.

“Modernity segregated use by space, and that’s a vast shift of what the modern city is. If you start segregating use by place, you start segregating people,” he explains. “The primary downside of that is that it kills off interaction, it kills off pedestrian life, it kills off diversity, and it kills off the complexity of the human experience. The class and racial segregation was intentional, and it’s hard to reverse those decisions.”

“The modernist project is toxic to community, and that was the point,” Graham continues. “If you want to reverse that, you’re going to have to reverse course on dividing space by use and by types of people and mix them back together. Modernism and community have had a complex relationship, and we’re paying for it now.”

Graham also suggests that one hazardous side effect of urbanization is population growth and the inability of cities to expand in response. His solution is an urban model that can “scale up,” but doesn’t repeat the mistakes of the modernist city.

“In 1960, 250,000 people lived in Nairobi, Kenya, and it is now inhabited by nearly 3.5 million people, but they haven’t built anywhere near enough new roads or sewer lines or proper housing to handle the growth. The overwhelming fact is population growth, and that population growth is coming with urbanization,” Graham maintains. “You have a situation in almost every country where cities are not keeping pace, or cities are built on a model that doesn’t work when scaled up.”

Graham explains that the challenge is returning a level of pre-modern function to modern cities—embracing new urbanism and community-based smart planning that has been emerging all over the world, what he calls a “self-organizing urban organism.”

“There’s this incredible urgency and creativity about how to rethink cities and how to reintegrate use and place,” he says. “That is the great riddle, the great success story. We are beginning to reinhabit our central cities and unsegregating our suburbs. It’s a positive, inspirational story, but also an aspirational one. As yet, it is a very small percentage of our footprint, but mostly we all live in the modernist dystopia of suburbs and shopping malls and parking lots. It’s a common experience, but it is part of a big long arc that we’ve gone through culturally.”

Currently Graham is working on a book on the history of Los Angeles through the neighborhood of Echo Park, which will rely on interviews and a house-by-house timeline of how the city evolved into what it has become versus what it was conceived to be in the 1880s. The book will focus on a local perspective, which will offer an understanding of the larger journey of American cities through racial, economic, political, and cultural changes that have taken place since the late 19th century.

Ultimately, Graham is fundamentally interested in Los Angeles and California. “It is so interesting, so complex, and continuously evolving and eluding simple solutions,” he says. “California is a complicated, interesting place. It’s quite a laboratory to be in to look at policy of all kinds.”

All photos of Wade Graham courtesy of Calvin Lim

Polish Edition of Dream Cities

Turkish edition of Dream Cities

Russian edition of Dream Cities